Are bottled water bottlers in the Western Cape exacerbating the drought in that region?

No, the activities of South African National Bottled Water Association (SANBWA) members in the Western Cape – located in Franschhoek, Paarl and Ceres – are not exacerbating the drought in the province.

The reasons for this are three fold:

• The water sources of SANBWA members nationwide (90% of which bottle from underground sources, that is, groundwater as opposed to surface water) must be audited to ensure long-term sustainability prior to membership being granted. All SANBWA members in the Western Cape bottle from groundwater sources.

• Groundwater is strongly buffered against drought influence. The various aquifers into which our members’ boreholes are drilled have enormous reservoir capacity, which provides the strong buffer against drought periods. The amount of water extracted is minuscule in comparison to both the reservoir as well as the annual replenishment. Note that even during droughts there is replenishment/recharge, albeit at a reduced rate. Recharge, or aquifer renewal, is replenished at between 5% and 20% a year depending on the underlying geology and topography. This is rainfall that soaks into the ground and into the aquifer, whereas surface water (dams and rivers, for example) is mainly dependant on reliable rainfall, and is therefore very susceptible to drought patterns.

• No water from any of these groundwater sources would naturally enter the municipal system via rivers and dams. Bottled water originates from sources licenced to private entities by the Department of Water & Sanitation specifically for the use of the water for commercial purposes (bottling water). The volumes extracted are monitored against the licensed limit.

It is also important to note, according to a presentation by BMI at Propak Cape in October 2017, the total size of the bottled water industry for 2016 was 502-million litres. This is not even equivalent to the 520-million litres DAILY target consumption for the City of Cape Town. SANBWA estimates that the total ANNUAL sales (during normal times) of bottled water in the Western Cape is about 30% of the national sales. This amounts to about 150-million litres ANNUALLY, or less than 30% of Cape Town’s DAILY target.

Are there other bottled waters or bottling systems that could be exacerbating the drought?

Yes, people must check the water source on the bottle of water before buying it because there are numerous offerings that are not bottled from sustainable sources, or are being bottled from the municipal supply. The water supply is usually from the tap and is thus from the municipal supply. Each litre produced uses more than 1 litre of municipal water as municipal water is used for rinsing and cleaning the bottling machine and the bottle.

Non-sustainable water sources could include:

• Shop-floor systems that use a combination of filters and/or ozone to purify tap water, which is then packaged in shop-branded bottles (bottled water) or re-filled into consumers’ containers (drinking water).

• Small retail outlets using a combination of filters and/or ozone to purify tap water, which is then packaged in shop-branded bottles (bottled water) or re-filled into consumers’ containers (drinking water).

• Counter-top filtration units used by restaurants, caterers and hotels, and linked to taps; the water is bottled in re-usable glass bottles and often closed with a Grolsch-type cap.

• Bottling companies or individuals starting up in response to the drought but do not adhere to South Africa’s legislation governing the bottled water industry. For example, they could be bottling from unlicensed, unprotected and unsustainable sources.

Has SANBWA had consultations with the city authorities, members or retailers about the pricing of bottled water?

It is illegal in South Africa to discuss, fix and or manipulate the price of goods. So, even if SANBWA was approached, it is legally obliged to decline to continue the discussion.

Are there measures in place to help supply water should Cape Town reach Day Zero?

SANBWA is currently in discussions with its members to identify areas of need, but it is important to note that the bottled water industry is too small to be the long-term solution to drought. It exists as a healthy beverage alternative, legislated as a food product, and cannot financially carry this burden, nor – given sustainability concerns – increase volumes beyond the licensed and sustainable yield.

Members have independent plans to donate and provide water at cost when possible. This includes donations to Water Shortage South Africa and Gift of the Givers, SAPS offices, Western Cape Disaster Management and Blood Bank stores, firefighting teams when they are out on call, and vulnerable communities such as the aged and the disabled.

Of concern is the misconception that bottling water is an inexpensive business, and that bottlers should easily be able to slash prices. In addition to the licensing fee, there is the considerable cost of ensuring sustainability of the source as well as the bottling, packaging and distribution. This includes the investment in plant and equipment, and compliance with health and safety regulations as well as packaging and labelling legislation. Another irrational assumption is that the industry can simply increase production to supply this spike in demand. The fact is that bottlers’ licences strictly regulate the volume they may extract for bottling (see question 1)

The cost of bottled water during this time could be dramatically reduced and supply ensured were Government to allow for an emergency water category that, for example, allowed bottlers to omit regular costly labels or alternative methods of bottling, such as a soft drink or beer company bottling their treated water for emergency handouts only. A major positive step would be for Government to reconsider proposed legislation, published in the Government Gazette Volume 631 Number 41381 on January 12 this year, whereby the Department of Water & Sanitation requires bottlers to reduce their water extraction by 40%, which would make it nearly impossible to keep up with the demand.

How much of South Africa’s water does the bottled water industry use?

The bottled water industry in South Africa is tiny compared to the total beverage market (including alcoholic) – 3.8% in 2016. Its total size nationally, not just in the Western Cape, for 2016 was 502-million litres. This ANNUAL figure is less than the 520-million litres DAILY target consumption for the City of Cape Town.

In addition to the fact that the bottled water industry comprises just 3.8% of the total packaged beverage industry in the country, it also has a very low water usage figure. The SANBWA average is 1.6:1 (or 1.6 litres of water used for every 1 litre of water bottled) but there are plants that achieve usages as low as 1.2:1.

More recent figures show that the South African bottled water industry across the three major bottled water categories namely Natural, Waters defined by Origin and Prepared), uses a modest 25.6 litres/second.

By comparison, a golf course uses 1 litre/second per hole or 18 litres/second for an 18-hole golf course, while the fruit export industry uses 0.5 litres/second/hectare. This means that the total South African bottled water industry’s use is equivalent to 1.4 golf courses … or just one 51-hectare farm.

According to BMI 2016 figures, category shares of the non-alcoholic beverage market are:

-

Sparkling soft drinks

69.3%

Ready-to-drink fruit juice

11.8%

Bottled water

8.9%

Dilutables

3.7%

Energy drinks

2.8%

Mageu

1.7%

Sports drinks

1.1%

Iced teas

0.9%

2012 figures from the Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries show that irrigated agriculture is the largest user of water in South Africa. These figures show that:

• 62% of available water is used for irrigation

• 27% is domestic and urban use

• 8% is used by mining, industry and power generation

• 3% is used by commercial forestry

Additionally:

• 30% of crops is produced through irrigation

• About 90% of fruit, vegetables and wine are produced under irrigation

Unfortunately, because the country wastes some 9-million tonnes of food a year – equivalent to 31.4% of average production – the fact that agriculture is the biggest consumer of water is a ‘double whammy’.

South Africa’s CSIR (Council for Scientific and Industrial Research) Natural Resources & the Environment Unit, Waste for Development Research Group has conducted research into the magnitude, cost and impacts of food waste in South Africa.

This research showed that the total water loss as a result of food waste in South Africa is equivalent to nearly 22% of the total water footprint, while the total cost to the country of food waste is some R61.5‑billion, or 2.1% of our GDP. Water loss as a result of wasting cereals is the highest (32%), followed by meat (26%). However, the cost impacts of fruit and vegetables are the highest (42%), followed by meat (32%).

While these are old figures, given the country’s population growth etc, it can be accepted that the percentages or proportions of water use have not changed.

How can consumers be assured of sustainable and safe alternate drinking water when the taps run dry?

By purchasing water that features the SANBWA logo, because this ensures source sustainability, quality and hygiene. By questioning claims made by cheap products. Environmental surveys to ensure source sustainability, the construction of a hygienic bottling facility etc cost far more than people factor into the price. Therefore, if the product is cheap, chances are the source is not what it is claimed to be, or the production facilities are not what they should be.

Can bottled/packaged water be compared to drinking/tap water?

Drinking/tap water and bottled/packaged water cannot be compared in terms of legislated category and quality because they need to comply with different standards and legislation.

The Department of Health views waters as follows:

• Tap water = drinking water and needing to comply with public water supply regulations

• Bottled water = packaged water and needing to comply with packaged water legislation

• Bulk water transported in tankers to distribute to rural or urban areas = public water supply and not within the scope of packaged water legislation

• Re-filling into the consumer’s own containers = drinking water not within the scope of packaged water legislation

• Bulk water in large bottles for office coolers = packaged water

• Bench-top treated waters and shop-floor treated waters bottled on site = packaged water

Water, in all its forms, is critical for human health. Bottled water does not compete with other waters but against other packaged beverages.

What is the average length of time water purchased in sealed bottles can be stored?

The Department of Health requires that packaged water contain both Production and Best Before dates. The Best Before date needs to be verified by a shelf life study. Still bottled water typically carries a one- to two-year Best Before date from the date of production. The water needs to be stored away from noxious fumes and out of direct sunlight.

How long can water stored in refillable bottles be kept?

The variables associated with refilling make it impossible to provide any guidelines on the expected shelf life. Some factors consumers would want to consider the microbial content of the source water and the container hygiene.

The type or source of water being used to refill the bottle is important. Is it a previously treated source of water, for example, and/or is it itself being stored and filled under hygienic conditions? In the absence of hygienic filling conditions or chlorine, any bacteria in the source will grow. Further, certain containers and their closures are hard to clean and are not sterile. And, has the container been used for other liquids – food or chemicals? These are just some of the factors that will impact the shelf life of the refilled water.

Finally, it is important to remember that, once a large-volume container containing water is opened, that water is regularly exposed to air (which is not sterile) and/or ‘germs’ from people handling the container. It would therefore be prudent to consume within a week of opening. This is not a scientific recommendation backed by research, because the different source/filling scenarios would impact the shelf life differently.

Can anyone with a natural source of water on his or her property (a dam, a spring, a borehole etc) bottle water and sell it in South Africa?

Only if they adhere to all legislative requirements. South Africa’s bottled water industry has to comply with some of the most stringent legislation in the world.

Firstly, the bottler needs to obtain a licence from the Department of Water & Sanitation that specifically allows for the water to be used for commercial purposes (bottling water). The volumes the bottler may extract are strictly monitored against the licensed limit.

Secondly, bottled water (or packaged water, as it is referred to in the legislation) is regarded as a food product and as such is governed by the Department of Health. All regulations pertaining to food preparation and safety, as well as packaging and labelling therefore apply. These include:

• A full hydrogeological survey to ensure source purity, protection and sustainability

• Adhering to microbiological legislation: Regulations Governing Microbiological Standards for Foodstuffs and related matters, R.692

• Conforming to treatment, labelling and chemical regulations as per R.718

• Conforming to labelling legislation as detailed in R.718 and Regulations Relating to Labelling and Advertising of Foodstuffs, R.146

• All food-hygienic design and handling legislation

How can you determine if the water you are buying is from a legitimate bottler or provider?

For bottled water, look for an indication of the source and the water category on the label. If they are not there, the bottler is not complying with packaging and labelling legislation. Ask to see the Certificate of Acceptability issued by the local municipality. Most importantly, look for the SANBWA logo. For water delivered by tankers to urban and rural areas, as well as outlets refilling consumers’ own containers, ask to see the licence granted by the Department of Water & Sanitation.

It is vital that consumers confirm that the water they are buying is labelled as ‘natural water’, ‘water defined by origin’ or ‘prepared water’, as ‘prepared water’ could be sourced from the municipal water supply. Anyone not prepared to disclose the source is most likely bottling from a tap or an unlicensed source.

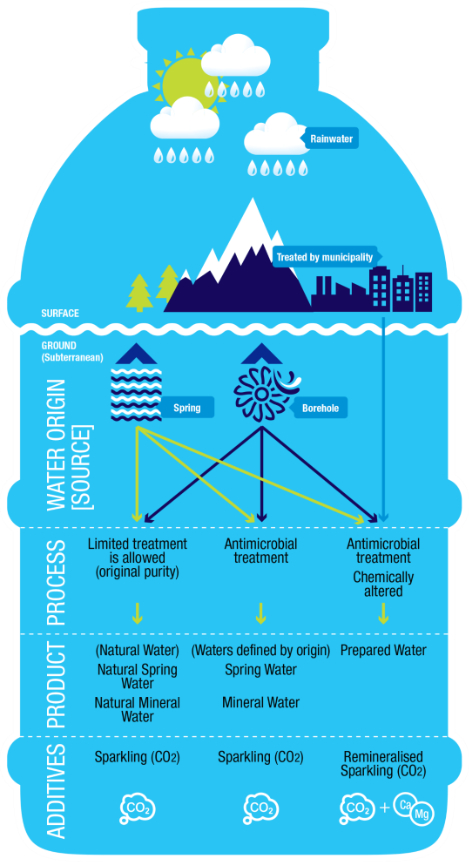

According to packaged water legislation, there main types of bottled water:

a. Natural Water

b. Water Defined by Origin

c. Prepared Water

a. Natural Water:

This is water of certain composition, obtained directly from a natural or drilled underground source, bottled near the source under hygienic conditions. Permitted treatment includes separation from unstable constituents (such as iron manganese, sulphur) by means of filtration or decantation, without modifying the original mineral content of the water.

Approximately 70% of all bottled water in South Africa is natural water.

b. Water Defined by Origin (including spring and mineral water):

This is water from a specific environmental source, such as a spring, without passing a through community water system. Treatment may not alter the essential physical-chemical characteristics or compromise the safety of the packaged water.

Permissible treatments include:

• Remove or eliminate dissolved gasses and unstable constituents (such as compounds containing iron, manganese, sulphur, excess carbonates).

• Reduction or separation of elements originally present in excess of maximum limits stipulated in SANBWA’s standards without modifying the general mineral composition of the water.

• A single or combination of antimicrobial treatments such as 0.2-micron filtration, heat sterilisation, UV treatment or ozonation

• Addition of air, oxygen, ozone or CO2.

Mineral water is bottled water, obtained direct from subterranean water-bearing strata, which contains mineral salts in various proportions, characterised by its mineral content of constant composition and temperature, taking into account natural cycles and fluctuations. It may be classified as a Natural Water or as Water Defined by Origin.

Spring water is bottled water sourced from an underground formation from which water flows naturally to the surface of the earth, and which is collected from the spring or from a borehole tapping the underground formation, and which may be classified as a Natural Water or as Water Defined by Origin.

Approximately 20% of all bottled water in South Africa is Water Defined by Origin.

c. Prepared Water:

This is water that has undergone antimicrobial treatment as well as treatment that alters the original physical or chemical properties of the water. Water bottled from an underground or a municipal source, that has undergone both reverse osmosis and ozonation as a minimum, would be categorised as Prepared Water.

Permissible treatments include:

• Any antimicrobial treatment. UV not allowed as a sole antimicrobial treatment.

• Treatments to remove or reduce chemical substances above maximum limits including treatments that modify the physiochemical composition and characteristics of the original water source – such as reverse osmosis.

• Remineralisation. The prepared packaged water must meet requirements for bottled water stipulated in SANBWA’s standards.

Approximately 10% of all bottled water in South Africa is Prepared Water. It is safe water that is used for drinking – thus it does not disappear during production and unavailable for consumer thirst.

In summary:

a. Natural Water – 70% of the total bottled water market

b. Water Defined by Origin – 20% of the total bottled water market

c. Prepared Water – 10% of the total bottled water market

There are other water ‘businesses’ that should be regarded as packaged water and should adhere to all packaged water legislation, but in most cases don’t.

These would be:

a. Retailers that package water in their stores (often using ozonators or filtering systems)

b. Restauranteurs who use counter-top filtration systems to package water into Grolsch-type glass bottles

The resultant product – regardless of whether it is ozonated, filtered or treated in any other manner – if it is filled to pose as bottled water is regarded by the South African authorities as ‘packaged water’ due to re-filling. These waters do not form part of the bottled water industry.

What does the SANBWA seal ensure?

The SANBWA seal ensures that the water source is environmentally sustainable. It also ensures that the water is free of chemical contaminants and microbiological impurities such as E.coli and that it has been bottled under hygienic conditions. It also confirms conformance to legislation and international standards and best practice.

The third version of the 92-page SANBWA Bottled Water Standard was published in May 2010 in consultation with NSF International, a global testing and certification company, and its affiliate on the African continent, NSF-CMi Africa (Pty) Ltd.

The technical advisory committee contributing to the development of the Standard included representatives from South Africa’s Department of Health, industry players and SANBWA experts. Updates to the Standard are published in the public domain on www.sanbwa.org.za.

The Standard reflects the current best practices for bottling water of all types in South Africa. It was always intended to be a pragmatic and useful document, and comparable to the main food and beverage standards in major markets around the world. Indeed, it has been benchmarked favourably against the Global Food Safety Initiative (GFSI) as including all the relevant control points of global standards such as BRC, IFS, ISO22000, SANS 10330, SANS 1049 and the NSF Beverage standards.

The major objective of the Standard is to provide existing and new bottlers with a vision for future improvements. It therefore addresses legal, food safety, quality and environmental issues by putting six main elements under the spotlight:

• management commitment

• quality systems

• HACCP

• resources (including prerequisite programs)

• operational controls

• environmental stewardship

The benefit of such a comprehensive and stringent standard is that compliance is an assurance to consumers and retailers (as well as bottlers of water) that all legal and food safety requirements have been met. It also more than meets SANBWA members’ responsibilities for due diligence, reduced food safety risks, and compliance with local and international standards and regulations in terms of South Africa’s Consumer Protection Act.

Importantly, the SANBWA Standard also provides the basis for SANBWA’s annual member plant audits. Conducted by an independent third-party food safety organisation reporting to SANBWA, the audit confirms members’ conformance with the technical and regulatory requirements. Members have to meet all legal requirements and minimum requirements set by SANBWA.

The scope of the Standard is extensive, covers bottled water as defined in packaged water legislation, from various water sources, as well as flavoured water in a single standard. Water sources include groundwater (subterranean) and surface water which has gone through municipal treatment.

A non-exhaustive excerpt from the content list demonstrates its inclusiveness: scope of the standard, classification of water, definitions and terminology, ownership and scope, administration and certification, language, membership, membership responsibilities, member registration, access and collaboration, unannounced audits, compliance criteria, corrective actions, certification, sanctions, appeals, confidentiality, management responsibility, quality management system, hazard analysis of critical control points, resource management, control of operations, environmental stewardship, water supply management, requirements and tests for source water, specification for natural source and final packaged water, specification and guidelines of microbiological test methods, requirements for labelling, packaging specification and guidelines for plastic packaging, and examples (of a food safety and quality policy, hazard analysis work sheet, risk assessment procedure, decision tree, process flow diagram for prepared water, process flow diagram for water from subterranean origin).

To allow for future growth in the industry, the Standard also provides for requirements for bottling of flavoured water (not currently covered under the legislation definition of packaged water).

What are the critical issues for consumers to consider when buying bottled water or alternative drinking water from suppliers that might not conform with legislation governing hygiene?

Consider the quality of the water source, the maintenance and cleaning of the production system, the purification processes, and the lack of preservatives and sterilisation.

There is no way of gauging how often the water sources for bench-top, and shop-floor or other systems are tested, and there’s no guarantee how often they change the filters they use.

Then, because some systems do not operate in a clean room environment, secondary contamination from air, poorly sterilised containers and handling is a major risk. The entire shop floor is the ‘open bottling area’, and this makes pest control and general hygiene challenging. Given that some systems mostly claim to remove chlorine, the water they offer effectively has no defence against the growth of bacteria and other microbiological organisms.

Simple removal of chlorine and microorganisms is a far cry from the chemical and microbiological requirements for packaged water. Maybe that’s not a problem in a restaurant, if you are guaranteed that the bottle you ordered is filled to order, but what if it’s the first task of the day? And, who knows how long the pre-filled bottles on the retail shelves have been standing there? Ideally, this category of water should be offered in a glass or jug, not a closed bottle system mimicking bottled water.

Plus, in the absence of chlorine, you do need (according to South African legislation) to disclose data on shelf life – data seldom seen.

Finally, if the system itself and the containers it is refilling are not properly cleaned and sterilised, they quickly become a breeding ground for bacteria. In fact, the Grolsch-type closure – not regarded as a hermetic seal by law – is one of the worst offenders, as that little rubber washer is notoriously difficult to sterilise.

If it is bulk-water supply, the hygiene of the vessel/tanks is critical.

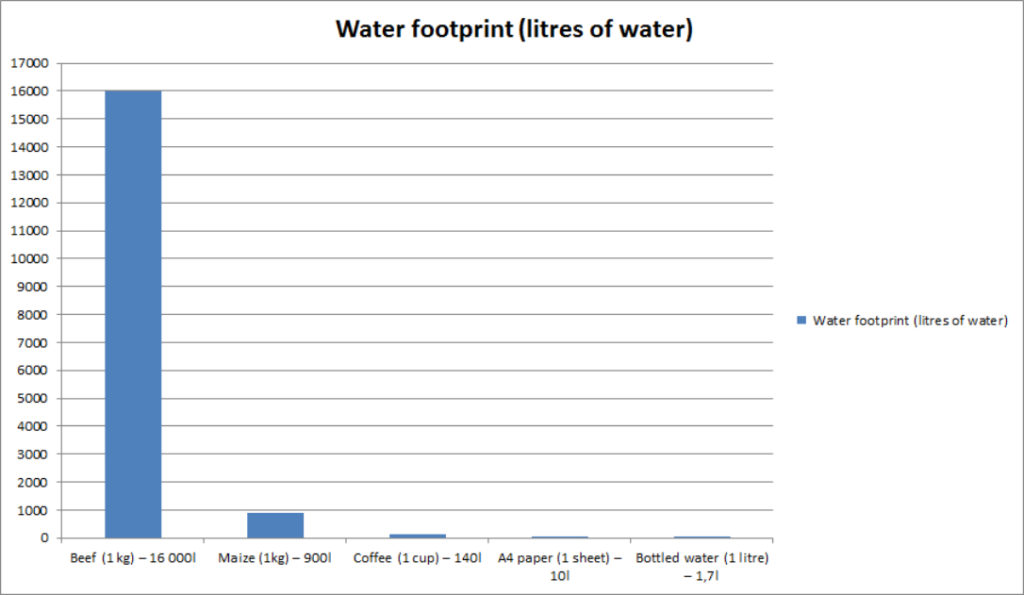

Does the bottled water industry have a extensive water footprint?

No, bottled water production is a very low water-use business versus other industries. According to http://www.waterfootprint.org/, to produce 1 kg of maize requires 900 litres of water, and to produce 1 sheet of A4 paper requires 10 litres of water. This source says that it requires just 1.8 litres to make a 1-litre bottle of water.

Continuing the comparison, excluding the packaging of these goods:

• the production of 1 kg of beef requires 16 000 litres of water

• the production of one cup of coffee needs 140 litres of water

In South Africa, the water usage figure for bottled water plants is typically 1.6:1 for one-way packaging. This means that, for every litre of water bottled, 600 ml is used for the cleaning and sanitation of plant and equipment, flushing toilets etc. There are, however, plants that achieve ratios of as low as 1.2:1.

What is SANBWA doing to combat the increased use of plastic that accompanies the increased sales of bottled water?

SANBWA has an environmental policy included in the SANBWA Bottled Water Standard, which are audited, and SANBWA and its members actively support recycling. SANBWA members support PET recycling by PETCO.

SANBWA’s environmental protocols address measures to ensure source sustainability and protection, water usage minimisation, energy efficiency, solid waste minimisation, and supporting post-consumer recycling initiatives even if the amount of plastic it utilises is small compared to the total amount of PET used in South Africa.

Therefore, members support PET bottle suppliers which contribute to the PETCO recycling levy.

They also follow ‘design for recycling’ principles to ensure that all their packaging components are recyclable. The post-consumer PET recycling rates in 2016 were above 55% (according to PETCO), an impressive figure.

Consumers must acknowledge that they are also responsible for waste and its recycling. SANBWA urges consumers to recycle as well as re-use plastic water bottles (provided they are washed regularly with soap and hot water).

How can consumers safely reuse and recycle their PET plastic water bottles during the drought?

With the increasing severity of the drought in the Western Cape, the storage and consumption of bottled water is expected to increase, and PET plastic bottles are a safe and convenient way to do this. PET bottles are not ‘single-use’ bottles and are not trash. When they are recycled, they are made into new bottles for water or beverages, or recycled into many new and useful products such as polyester fibre for duvets and pillows, jeans and t-shirts, and re-usable shopping bags.

PETCO’s tips to Capetonians include:

• If collecting from a water point, it will be helpful to re-use your PET bottles, especially the 5 litre bottles.

• When re-using PET bottles for water storage, please ensure that they are clean. PET bottles are safe for use and reuse so long as they are washed properly with detergent and a little water to remove bacteria, as you would any other container.

• When dropping PET bottles off for recycling, there is no need to wash them.

• Please do not throw the bottles away when you are finally finished using them – bottles should never be sent to landfill sites or end up as litter in the environment. PET bottles are fully recyclable when basic design principles are followed. Take your bottles to one of the following City of Cape Town drop-off facilities where they will be sent to PETCO member companies for recycling: www.capetown.gov.za/Work%20and%20business/See-all-City- facilities/Our-service-facilities/Drop-off%20facilities

• Please leave the caps on, as these are also recyclable.

PET bottles are safe to use. There has been a lot of confusion about what is in plastic containers, since concerns were raised about the safety of polycarbonate products containing Bisphenol-A (bPA). There is no connection between PET plastic and Bisphenol-A. Bisphenol-A is not used in the production of PET material, nor is it used as a chemical building block for any of the materials used in the manufacture of PET.

Who are SANBWA’s members?

These are the SANBWA registered member bottlers. Their brands can be bought with confidence knowing they are bottling sustainably: aQuellé, Bené, Bonaqua, Ceres Spring Water, Di Bella Spring Water, Nestlé Pure Life, Aquabella, La Vie De Luc, Cape Aqua, Oryx Aqua, Thirsti and Valpré.